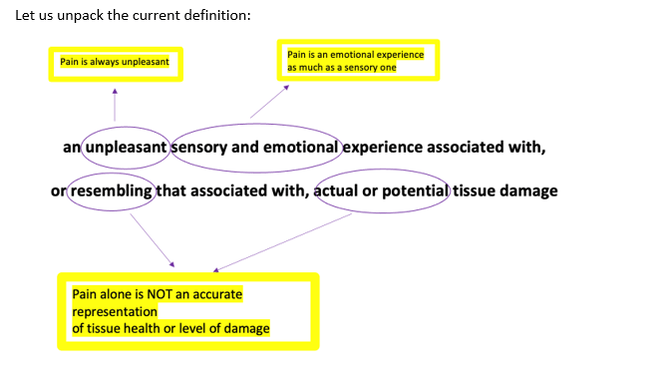

“an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” – International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), 2020

Defining pain has been and continues to be a topic of debate within the scientific community, this is because it is so subjective. Whilst almost everyone has experienced pain, reasons how and why it presents vary widely.

An important note made alongside the current definition is that pain is best understood within an individual’s biopsychosocial context. To understand a person’s circumstances is to understand their pain.

A big misconception about pain is that its presence and severity indicate the presence and severity of tissue damage. Pain and pathology are often poorly related. Pathology is not a prerequisite for pain and pain cannot be measured by tests and scans looking for physical changes.

Here is a great time to highlight that findings on a scan cannot tell you that you should be experiencing pain. Studies show that at LEAST 50% of people walking around totally pain free would have abnormal findings on a scan (Brinjinki et al., 2015).

Pain is:

•a warning signal with a protective function

•how your brain alerts your body of a perceived threat

• an essential part of survival

However, in some cases, pain can progress from being necessary and protective to unnecessary and dysfunctional. This is where the concepts of acute and chronic pain come in. To understand these concepts a basic understanding of pain signalling is required.

The pain pathway:

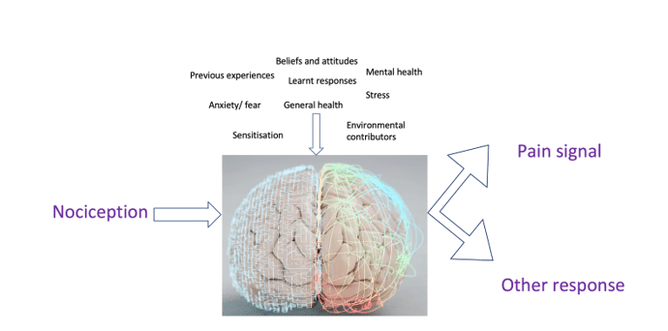

Every tissue in the body contains nerves specifically designed to identify potentially harmful stimuli = nociceptors. When exposed to a stimulus the nociceptor is activated sending an alert in the form of an electrical impulse to the spinal cord which passes that alert on to the brain. This signalling process is called nociception. Nociception does not automatically equal pain

The brain must take this signal and interpret it. It may send a pain signal, alerting the body of the perceived threat or perhaps opt for another course of action, telling the body to readjust in the chair or move away from a heater that is warming. This decision is influenced by a huge array of factors.

Acute pain:

In an acute context the job of this pain signal is to prevent any further damage from occurring, an essential protective response.

Take a sprained ankle for example; nociceptors within the overstretched ligaments and soft tissue are activated firing alerts via the spinal cord and the brain. The brain interprets these alerts and responds with a pain signal to protect the area whilst the body begins the healing process. The pain generated creates a hyperawareness of the ankle ensuring caution whilst this process takes place.

A key step in this process is that the brain stops sending the pain signals once the area is healed and they are no longer required.

But sometimes it doesn’t…..

In some situations, the pain continues even once the tissues have healed, and the threat has subsided. This is where the concept of chronic pain comes in.

Chronic pain:

Chronic pain is a much more complicated topic but key points to understand are:

•Chronic pain is pain that proceeds past the normal length of time expected for the tissues to heal

•Pain signals are no longer protective and have no obvious function

•Chronic pain is understood as multi-faceted and multi-dimensional. There are a range of individual factors contributing to the severity and presentation of the pain. These can range from psychological, environmental, social and biological

•The presence of persistent pain can result in structural changes to the components of the pain pathway. These create an increased awareness and reactiveness within the nervous system. This process is described as sensitisation.

•Pain can become a learnt behaviour, the longer the pain signals are produced the better your body gets at producing them. Pain produces more pain

Low back pain example:

Take a person who has an incident of trauma, perhaps lifting and twisting injury which caused local tissue damage and an acute onset of pain. The body works to repair the area, the tissues heal, and the acute pain eventually goes away.

However, they are left with a slight niggle now and then, indicating the nervous system is more aware of that area than it was before. They are also more hesitant to lift heavy objects. The brain has learnt from the incident that lifting may lead to tissue damage and wants to stop that happening again. This means in the future it may be much quicker to send a pain signal as a response to lifting or even bending forwards, despite no tissue damage occurring. This can lead to recurring episodes of low back pain without significant onset.

The initial incident may have also created a lot of stress for the person. The brain may now link stress with low back pain, leading to back pain during periods of increased psychological stress.

This commonly leads to the development of attitudes and beliefs that someone has a “bad back” or a “weak back” or that movements such as bending forwards are bad for them. These attitudes fed into the pain experience leading to more pain, decreased confidence, decreased function, and increased disability.

Brains are smart, and their sole job is to learn and adapt. Its why you only touch a hot stove top once as a child. However, in this case and many chronic pain cases the brain has failed to account for the fact the body is healed and strong and it doesn’t need protection from bending forwards, it is more than capable of doing that without injury. The hyperresponsiveness is not serving a useful function. Therefore, retraining the brain after injury is a key aspect of recovery.

How osteopaths can help:

It is important to receive professional advice to help manage and relieve pain early. It is equally as important to begin moving again as soon as possible under the guidance of a professional.

Osteopaths are trained to assess a person holistically. Time is taken to gather a detailed history and assess all potential contributors to a pain presentation. A management plan is then developed and tailored to the individual which may include referral to other practitioners to develop a team approach to recovery. We are here to help!

All pain is real pain, it is a valid unpleasant sensory and emotional experience and obtaining relief from pain is a human right.

References:

Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P. H., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B. W., Chen, L. E., Deyo, R. A., ... & Jarvik, J. G. (2015). Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. American journal of neuroradiology, 36(4), 811-816.