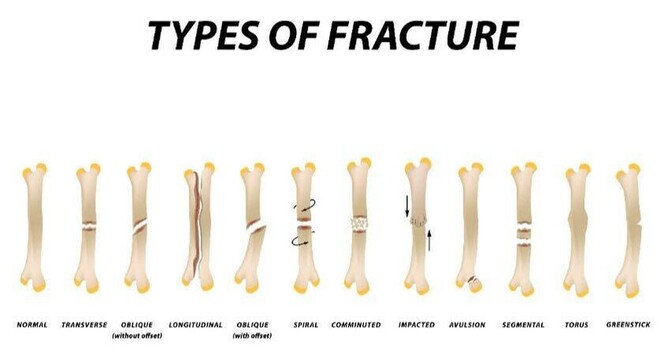

Bone injuries and fractures can be classified in many different ways, based on the way the bone broke or why it broke. Following are some commonly used terms that might be good to know to understand your own injury. Fracture is defined as cracking or breaking of a hard object, in this case the bone. That is, fracture can be either partial or full thickness rendering the bone in two (or more) pieces.

Pathologic fracture means that the bone breaks in an area that has been weakened by another disease process.

Stress fracture is a microfracture caused by repetitive stress (like sports, heavy labour) on the bone. If the bone is not given rest and time to heal and the forces on it continue it can progress to a full fracture.

Avulsion fracture happens when a tendon or a ligament is put under a lot of stress and rather than rupturing the tendon or ligament it pulls away the part of the bone it attaches to.

Compression fracture means that the bone size is decreased from trabecular compression (bones inner porous structure has been compressed). This happens most commonly in the vertebrae of osteoporotic patients.

Greenstick fracture happens in children and means that the trabeculae (porous inner part of the bone) has buckled but the bone isn’t completely broken.

Fractures heal through physiological processes that are in their essence very similar to how skin wounds, or any other tissue, in our body heals. The healing process is mainly determined by the periosteum that is the outer fascial (connective tissue) layer of the bone. Periosteum is the primary source of the cells that help to build the new bone, although some of those cells do come from bone marrow and other places in the bone as well.

Bone heals best when the edges of the two fractured pieces are close together and don’t move too much. This is why immobilisation with a cast helps the healing process. Sometimes the two edges of bone are not aligned or are hard to immobilise with a cast, and that’s when surgery may be needed to aid the healing. Nowadays patients are encouraged to move and put weight on the affected bone as soon as tolerable (starting slowly and carefully progressing) because it’s now known that excessive immobilisation can have negative effects on healing, including losing muscle and bone mass. Progressively putting weight on the bone helps to build it stronger when it’s time. Always listen to the advice from your orthopaedist and manual practitioner about when you’re ready to do this, every case is different.

Bone healing is affected by the age, nutrition and systemic diseases of the individual. Younger people heal faster, whereas osteoporosis and diabetes, among others, can slow the healing process. Several different hormones (like thyroid hormone, growth hormone, calcitonin, oestrogen and cortisol) also play significant roles in bone healing.

Fractures heal in 3 phases:

Inflammation/reactive phase is the first stage and lasts up to three days after the fracture occurred. In this phase blood cells fill the adjacent tissue, blood vessels constrict to stop any further bleeding and the blood forms a clot (haematoma). In the later stages granulation tissue forms to connect the two edges of the bone.

Proliferation/reparative phase can take up to 6 weeks. In this phase the cells of the outer fascial layer of the bone, the periosteum, replicate and blood vessels start to grow. The granulation tissue formed in the first phase develops into cartilage and the periosteal cells develop into cells that produce new bone and start forming woven bone that is found in places where bone growth happens rapidly. Eventually the cartilage and woven bone bridge the fracture gap. The cartilage and woven bone is then replaced with stronger lamellar bone. This is called hard callus and is the equivalent of a scar on skin.

The final phase of bone healing is called the remodelling phase. Here the callus formed in the second stage of healing is replaced with compact bone and remodelled into a new shape that closely duplicates the bone’s original shape and strength. The bone in the site of healing is often a bit thicker than the original bone was.

Stages of Healing Bone Fracture

What you can do to aid bone healing

Nutritionally, making sure you have enough calcium, magnesium, zinc, phosphate, carbohydrates and proteins is going to help the healing process by providing the building blocks needed for bone growth.

Be sure to avoid re-injury by having patience with your healing process and listening to the advice of your orthopaedic doctor and manual practitioner.

Making sure that your diabetes and possible other conditions are managed optimally is going to help a lot too.

Seeing an osteopath is going to help you handle the compensations that happen in your body as a result of using your body differently after the injury. It helps to ease off aches and pains and also increases blood flow and the healing process. Your osteopath and physiotherapist work together to give you a treatment and rehabilitation programme that gets you back to your normal activities as soon as possible.