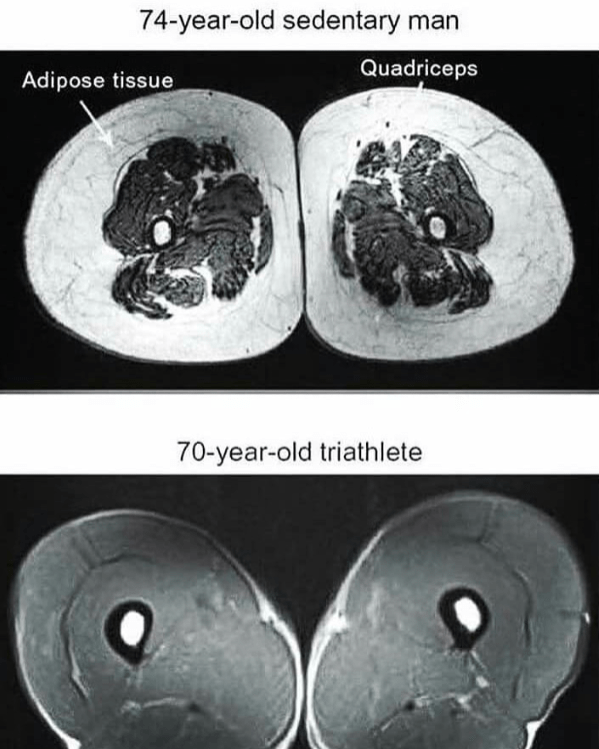

The ageing process affects the entire body, including organs, the nervous system, and the musculoskeletal system. As we age, muscle tissue undergoes degenerative changes that primarily involve the loss of muscle mass and strength, a process known as sarcopenia [1].

The reduction of muscle mass, primarily in the lower extremities, begins around the ages of 25–30. This reduction is accompanied by a decrease in contractile tissue and an increase in non-contractile tissue, such as adipose tissue and other types of connective tissue [2].

Reduction of Strength

With age, the number of muscle fibres decreases significantly. The decrease in muscle mass is primarily due to the loss of fast-twitch fibres, also known as Type II fibres, resulting in a reduction of muscle strength at a rate of approximately 1% per year. [3]

Changes in Muscle Fibre Diameter

Type IIA and IIB muscle fibres decrease with age, thereby increasing the amount of Type I fibres of smaller diameter. Recent research suggests that this increase in Type I fibres may lead to a potential deterioration of muscle quality, loss of balance, and lack of coordination in simple tasks [4].

Motor Unit

Current literature indicates that the decrease in muscle fibres is due to the loss of motor neurons. In a young, healthy individual, there is a balance between the denervation and reinnervation of muscle fibres; however, as we age, the cycle of denervation seems to surpass that of reinnervation, leading to muscle deterioration.

A 60-year-old person has approximately 25% to 50% fewer motor neurons than a 20- year-old, with the greatest loss occurring in the distal fast-twitch motor neurons. With the decrease in motor neurons, some denervated fast-twitch muscle fibres undergo a process called apoptosis (cell death), while others regenerate as slow-twitch motor neurons [5].

Changes in the Endocrine System

As we age, changes occur in the efficiency and production of certain hormones [6].

1. Increased insulin resistance

2. Decrease in growth hormone

3. Reduction of oestrogen and testosterone, approximately 1% per year starting at age 30

4. Vitamin D deficiency

5. Increase in parathyroid hormone

Tendons

The water content of tendons decreases as we age, making them stiffer and more prone to injury [7]. More information about tendon issues can be found in these blogs: tendinopathy and tendinitis, tendinosis, and tendinopathies.

How to Prepare the Body for Physical Activity

Progressive strength training is an effective intervention to improve physical performance in older adults, including an improvement in strength for performing simple and complex activities [8]. Current recommendations advise strength exercises that include the major muscle groups, a minimum of two times per week, performing 1 to 3 sets, and completing 8 to 12 repetitions per set [9]

Warm-Up

Current guidelines proposed by The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) for warming up senior athletes recommend a very gradual exposure to physical activity for a total duration of 15 minutes. The warm-up should include some form of aerobic exercise, such as cycling, rowing, or light jogging. It should focus on the muscles and joints to be used during the main activity. The purpose of the warm-up is to prepare the body for more intense activity, so it should be vigorous enough to elevate the heart rate.

References:

1. Pacifico J, Geerlings MAJ, Reijnierse EM, Phassouliotis C, Lim WK, Maier AB. Prevalence of sarcopenia as a comorbid disease: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Exp Gerontol [Internet]. 2020;131(110801):110801. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2019.110801

2. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing [Internet]. 2019;48(1):16–31. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

3. Lexell, J., Taylor, C. C., & Sjöström, M. (1988). What is the cause of the aging atrophy? Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 84(2-3), 275-290. doi:10.1016/0022-510X(88)90053-2.

4. Lee S. Changes in muscle fiber composition with aging. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2006;27(4):253–9.

5. Hepple, R. T., & Rice, C. L. (2016). Motor unit and muscle fiber changes with aging. The Journal of Physiology, 594(18), 5257-5268. doi:10.1113/JP272295

6. Visser, M., Deeg, D. J. H., & Lips, P. (2003). Hormonal changes in aging: Implications for muscle health. Journal of Endocrinology, 179(3), 327-335. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1790327.

7. Genet, F. (2019). Tendon changes with aging: Implications for injury. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 37(4), 789-795. doi:10.1002/jor.24266.

8. Suetta, C., Hvid, L. G., Aagaard, P., & Kjær, M. (2004). Strength training for older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(2), 123-130

9. Kathirgamam V, Ambike M, Bokan R, Bharambe V, Prasad A. Analyzing the effects of exercise prescribed based on health-related fitness assessment among different somatotypes. J Health Sci [Internet].